Tiny device promises new tech with a human touch

Engineers at RMIT University have invented a small ‘neuromorphic’ device that detects hand movement, stores memories and processes information like a human brain, without the need for an external computer.

Smart spongy device captures water from thin air

Engineers from Australia and China have invented a sponge-like device that captures water from thin air and then releases it in a cup using the sun’s energy, even in low humidity where other technologies such as fog harvesting and radiative cooling have struggled.

Gas-sensing capsule takes another big step from lab to commercialisation

An ingestible gas-sensing capsule that provides real-time insights into gut health has moved closer to market with RMIT University transferring IP ownership to medical device company Atmo Biosciences.

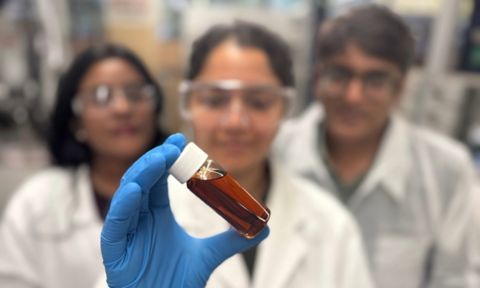

Aussie tech helps make bio-oils for greener industrial applications

Australian technology developed at RMIT University could enable more sustainable and cheaper production of bio-oils to replace petroleum-based products in electronic, construction and automotive applications.