RMIT researcher Dr Torben Daeneke said converting CO2 into a solid could be a more sustainable approach.

“While we can’t literally turn back time, turning carbon dioxide back into coal and burying it back in the ground is a bit like rewinding the emissions clock,” Daeneke, an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow, said.

“To date, CO2 has only been converted into a solid at extremely high temperatures, making it industrially unviable.

“By using liquid metals as a catalyst, we’ve shown it’s possible to turn the gas back into carbon at room temperature, in a process that’s efficient and scalable.

“While more research needs to be done, it’s a crucial first step to delivering solid storage of carbon.”

How the carbon conversion works

Lead author, Dr Dorna Esrafilzadeh, a Vice-Chancellor’s Research Fellow in RMIT’s School of Engineering, developed the electrochemical technique to capture and convert atmospheric CO2 to storable solid carbon.

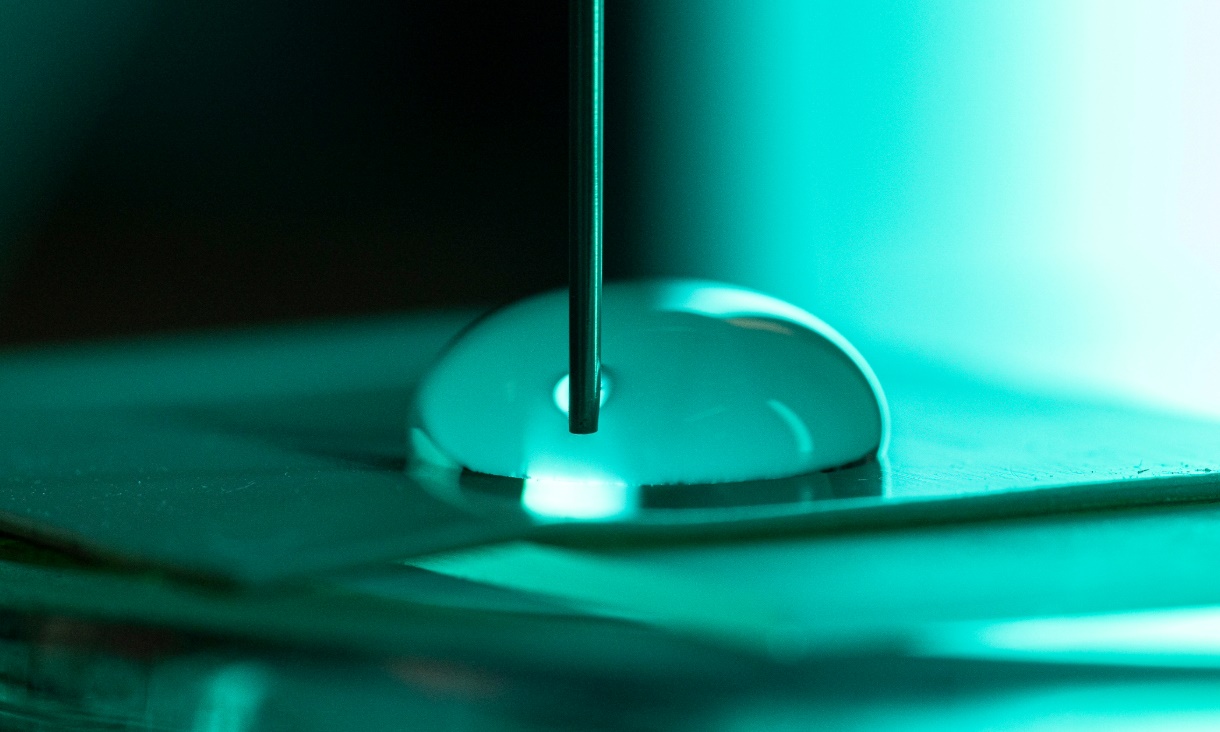

To convert CO2, the researchers designed a liquid metal catalyst with specific surface properties that made it extremely efficient at conducting electricity while chemically activating the surface.

The carbon dioxide is dissolved in a beaker filled with an electrolyte liquid and a small amount of the liquid metal, which is then charged with an electrical current.

The CO2 slowly converts into solid flakes of carbon, which are naturally detached from the liquid metal surface, allowing the continuous production of carbonaceous solid.

Esrafilzadeh said the carbon produced could also be used as an electrode.

“A side benefit of the process is that the carbon can hold electrical charge, becoming a supercapacitor, so it could potentially be used as a component in future vehicles.”

“The process also produces synthetic fuel as a by-product, which could also have industrial applications.”

The research was conducted at RMIT’s MicroNano Research Facility and the RMIT Microscopy and Microanalysis Facility, with lead investigator, Honorary RMIT and ARC Laureate Fellow, Professor Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh (now UNSW).

The research is supported by the Australian Research Council Centre for Future Low-Energy Electronics Technologies (FLEET) and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Electromaterials Science (ACES).

The collaboration involved researchers from Germany (University of Munster), China (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics), the US (North Carolina State University) and Australia (UNSW, University of Wollongong, Monash University, QUT).

The paper is published in Nature Communications (“Room temperature CO2 reduction to solid carbon species on liquid metals featuring atomically thin ceria interfaces”, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-08824-8).