Daily, without your knowledge, computer algorithms are using your data to predict your habits, preferences and behaviour.

They decide your love of YouTube cat videos means you'll be spammed by Whiskers ads, or that your Beatles downloads mean you want to hear Paul McCartney's 100th single.

If you enjoy the music being recommended, or don't find ads mirroring your web browsing creepy, then you probably don't mind.

But decision-making by algorithms goes much further.

Algorithms are deciding who passes passport control, who gets debt collection notices, home loans and insurance cover, even who gets targetted by police and how long their prison sentence might be.

Recently, it was revealed that algorithms were telling period tracking apps to inform Facebook when you might be pregnant.

An algorithm is basically a set of instructions for a computer on how to handle the data it receives.

As more and more systems become automated and personalised those inputs are increasingly our personal data: mobile phone location, social media or app usage habits, web browsing history and even health information.

The problem is you never know exactly how an algorithm processes your data to arrive at its decision: whether your mortgage application was rejected based on your history of unpaid bills or the colour of your hair.

In fact, you have no input at all into the decision-making process and can guarantee your interests will always come behind those who developed the app.

A group of leading computer scientists have recently been discussing the need to better protect ourselves in this emerging system.

They say that without taking action, we will lose control over both our personal data and transparency in the decisions being made about us.

One of the solutions promoted by RMIT University's Associate Professor Flora Salim, UNSW's Professor Salil Kanhere and Deakin University's Professor Seng Loke is to program our own algorithmic guardians.

What is an ‘algorithmic guardian’?

Algorithmic guardians would be personal assistant bots or even holograms that accompany us everywhere, and alert us to what’s going on behind the scenes online.

These guardians are themselves algorithms, but they work for us alone, programmed to manage our digital interactions with social platforms and apps according to our personal preferences.

They could alter our digital identity according to our wishes, apply different settings to different services and even make us recognisable or anonymous when we choose to be.

Our guardians could ensure our backups and passwords are safe, and allow us to decide what is remembered and what is forgotten in our online presence.

In practical terms, an algorithmic guardian would:

alert us if our location, online activity or conversations were being monitored or tracked, and give us the option to disappear

help us understand the relevant points of long and cumbersome terms and conditions when we sign up to an online service

give us a simple explanation when we don’t understand what’s happening to our data between our computer, phone records and the dozens of apps running in the background on our phones

notify us if an app is sending data from our phones to third parties, and give us the option to block it in real time

tell us if our data has been monetised by a third party and what it was for.

Algorithmic guardians are envisaged as the next generation in current personal assistants such Siri, Alexa or Watson.

They don't need to be intelligent in the same way as humans, just smart in relation to the environment they inhabit - recognising other algorithms and explaining what they're doing.

Without this accountability, key moments of our lives will increasingly be mediated by unknown, unseen, and arbitrary algorithms.

Algorithmic guardians would take on the important role of communicating and explaining these decisions.

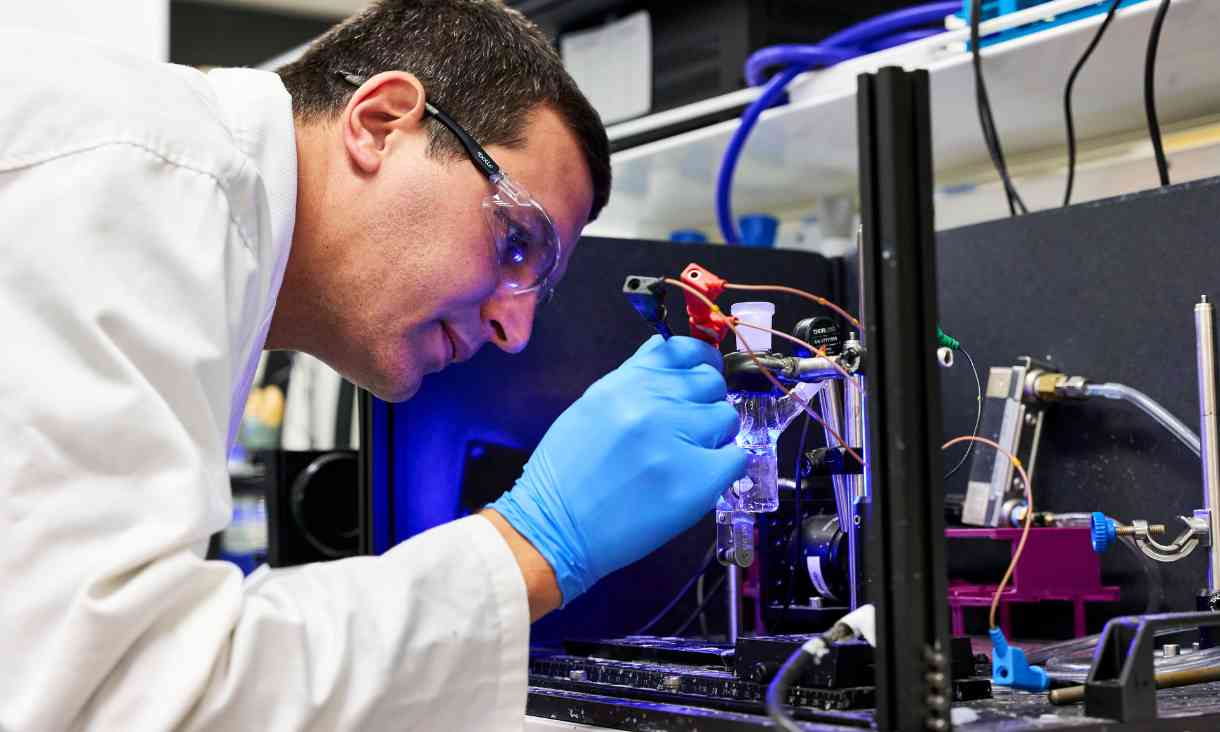

Explainable machine learning, which tries to provide insight into how an algorithm arrives at its final decision, is an area of increasing intererst and activity in AI research.

Now that algorithms have become pervasive in daily life, explainability is no longer a choice, but an area urgently requiring further attention.

When will algorithmic guardians arrive?

The technology to enable algorithmic guardians is emerging as we speak, what’s lagging is the widespread realisation that we need them.

You can see primitive versions of algorithmic guardians technology in digital vaults for storing and managing passwords, and in software settings that give us some control over how our data is used. But in the era of pervasive computing, something more comprehensive is required.

The team says we need to develop specific algorithmic guardian models in the next couple of years to lay the foundations for open algorithmic systems over the coming decade.

Surely the demand is there, or is it?

Notions of privacy have radically transformed over the past decade.

Could it be that in another decade we won’t even care that every system knows everything about us and does whatever it wants with that information, because mostly it works out okay?

This article is adapted from a piece appearing in The Conversation, written by Salim, Kanhere and Loke.

Story: Michael Quin