Animal behaviour from a physicist’s lens

We suspect Einstein’s letter is a response to a query he received from Glyn Davys. In 1942, as WWII raged, Davys had joined the British Royal Navy. He trained as an engineer and researched topics including the budding use of radar to detect ships and aircraft. This nascent technology was kept top secret at the time.

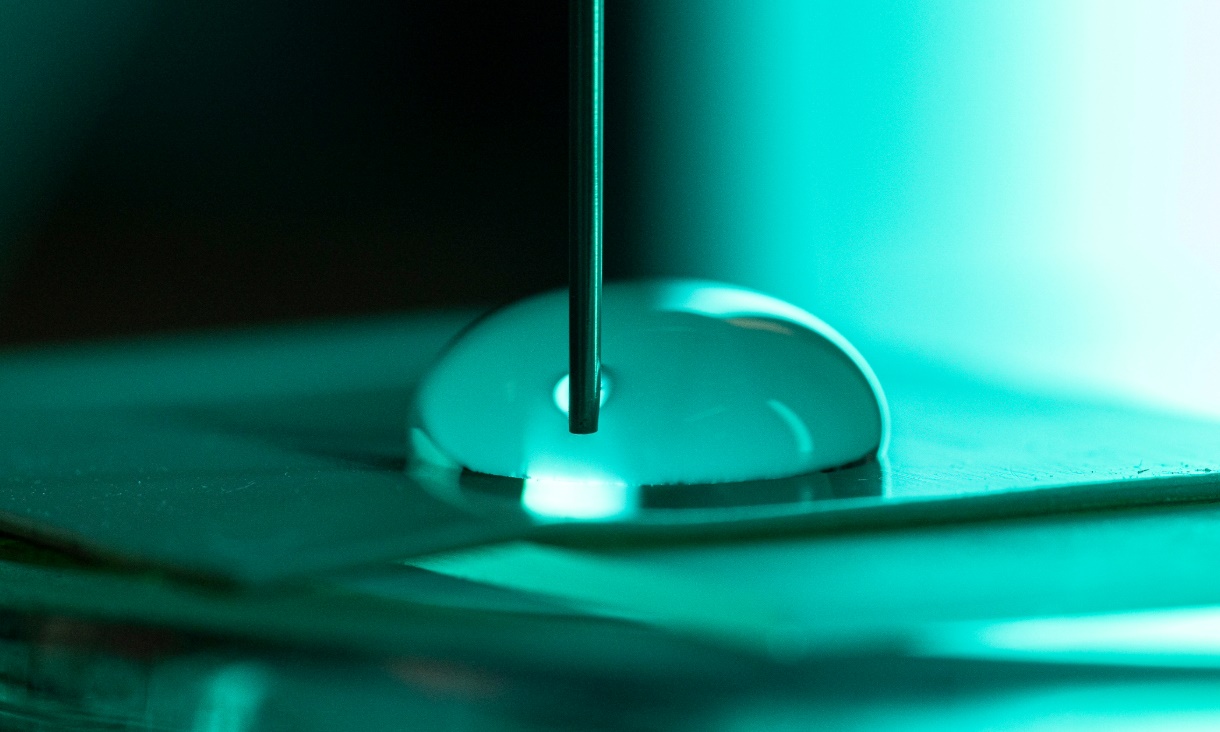

By complete coincidence, bio-Sonar sensing had been discovered in bats at the same time, alerting people to the idea that animals may have different senses from humans. While any previous correspondence from Davys to Einstein appears lost, we were interested in what may have prompted him to write to the famous physicist.

So we set out to trawl through online archives of news published in England in 1949. From our search we found von Frisch’s findings of bee navigation were already big news by July of that year, and he had even been covered in The Guardian newspaper in London.

The news specifically discussed how bees use polarised light to navigate. As such, we think this is what spurred Davys to write to Einstein. It is also likely Davys’s initial letter to Einstein specifically mentioned bees and von Frisch, as Einstein responded: “I am well acquainted with Mr. v. Frisch’s admirable investigations”.

It seems von Frisch’s ideas about bee sensory perception remained in Einstein’s thoughts since the two scientists crossed paths at Princeton six months earlier.

In his letter to Davys, Einstein also suggests that for bees to extend our knowledge of physics, new types of behaviour would need to be observed. Remarkably, it is clear through his writing that Einstein envisaged new discoveries could come from studying animals’ behaviours.

Einstein wrote:

It is thinkable that the investigation of the behaviour of migratory birds and carrier pigeons may someday lead to the understanding of some physical process which is not yet known.

Einstein ideas seem right, yet again

Now, more than 70 years since Einstein sent his letter, research is indeed revealing the secrets of how migratory birds navigate while flying thousands of kilometres to arrive at a precise destination.

In 2008, research on thrushes fitted with radio transmitters showed, for the first time, that these birds use a form of magnetic compass as their primary orientation guide during flight.