Slippery maths used to argue Sydney sea level has fallen

The claimThe sea level in Sydney Harbour fell by 6 centimetres between 1914 and 2019. |

Our verdictFalse. Data from the Bureau of Meteorology shows the sea level around Sydney rose by 8 centimetres over the period. |

By Frank Algra-Maschio

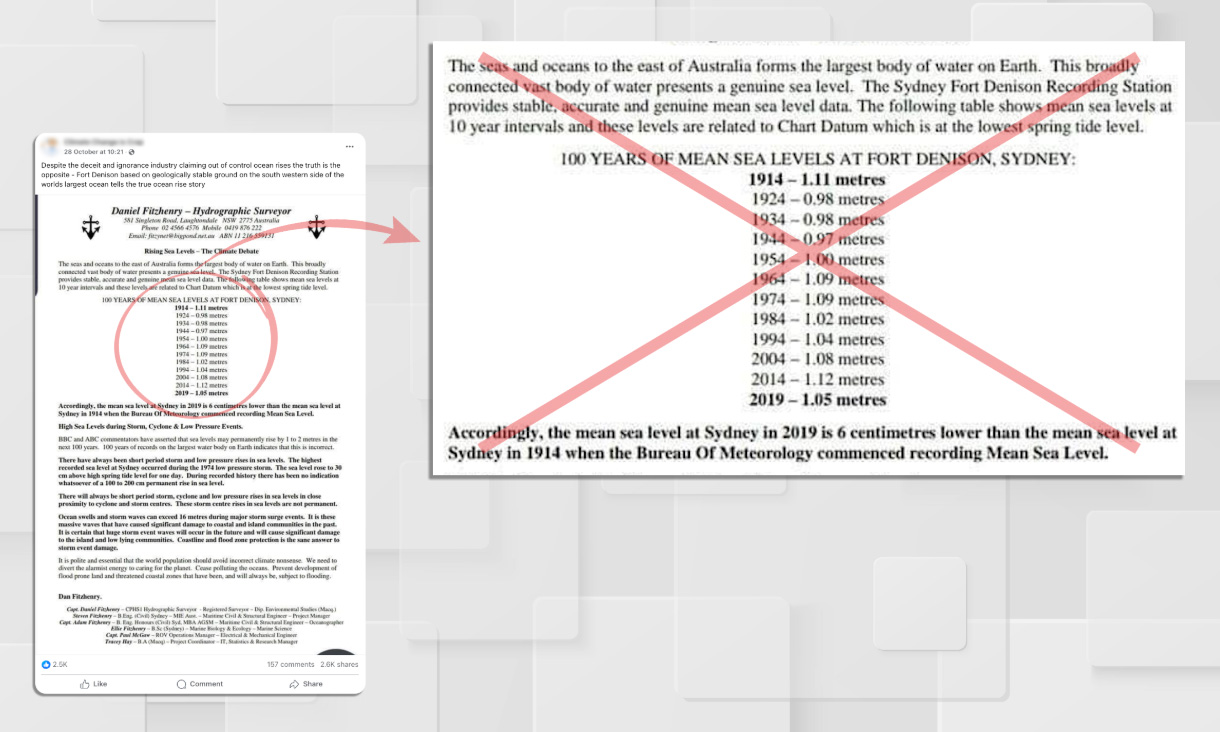

A viral document purporting to show evidence that the sea level has fallen in Sydney Harbour over the past 105 years uses shonky maths to argue climate change predictions are flawed.

Facebook users have shared the document more than 2,000 times, with some claiming it “tells the true ocean rise story” or “makes every single claim over the past 40 years about sea level rises as [sic] total rubbish.”

But the document, which carries the names of a hydrographic surveyor and several engineers, misrepresents Australia’s official data on sea levels.

Experts told RMIT Lookout that sea levels are instead rising almost everywhere and warned against relying on cherry-picked data that draws the wrong conclusions.

Getting the numbers right

The document presents a series of mean, or average, sea-level estimates, based on data it says was collected from a tide gauge at Fort Denison in Sydney Harbour between 1914 and 2019.

“[T]he mean sea level at Sydney in 2019 is 6 centimetres lower than the mean sea level at Sydney in 1914,” the document says, claiming the sea level fell from 1.11 metres to 1.05 metres over the period.

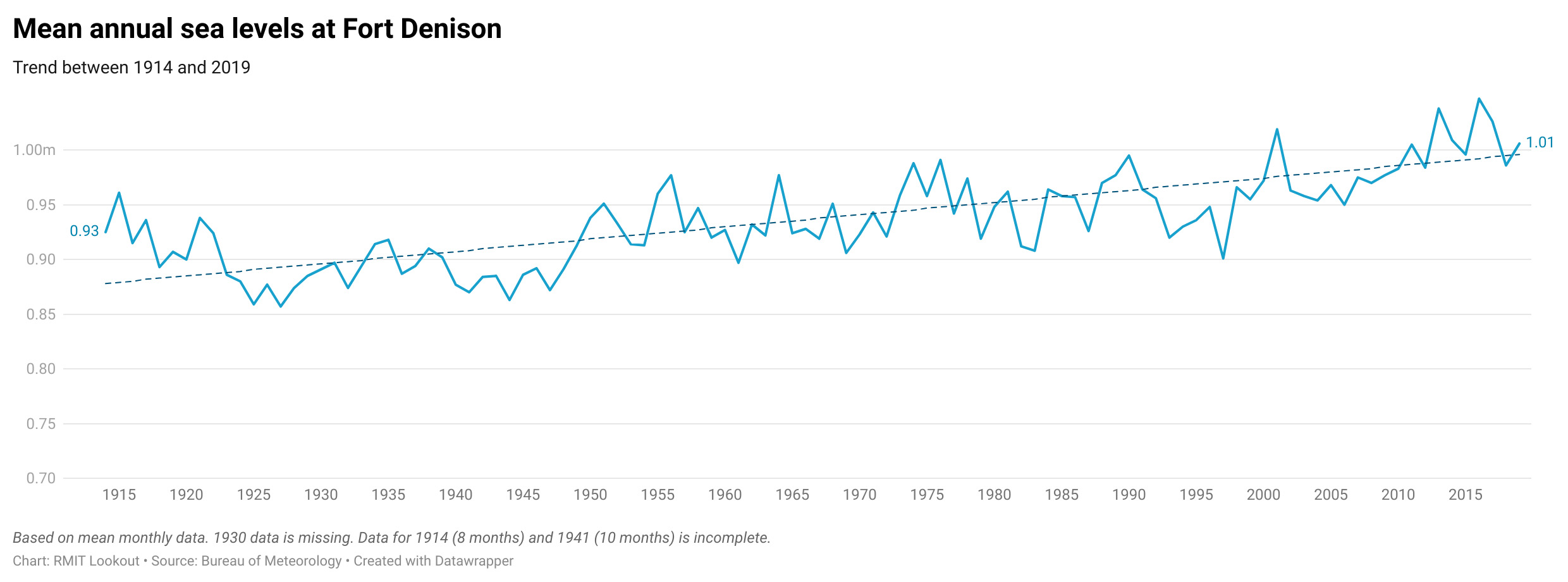

But official data from the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) shows a clear rise of just over 8cm in the mean sea level recorded at Fort Denison between 1914 and 2019.

Selectively quoted data misrepresents sea levels

The Bureau of Meteorology records observations of sea levels taken at various sites around Australia, including Fort Denison, and publishes them as monthly averages.

The social media document claims to show annual mean sea-level figures “at 10-year intervals”. But these figures are not annual averages. Indeed, most of the figures appear to have been chosen from one month every ten years in order to present decreasing annual figures.

On inspection, the document appears to have used data from May for 1914, March for 2019, April for the years 1924-1944 and June for the years 1964-1984. In all but two years (1984 and 2019), the numbers match the month with the highest sea level.

John Church, an expert contributor to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report and emeritus professor at the University of NSW’s Climate Change Research Centre, told RMIT Lookout that the document appeared to have “selectively quoted” sea levels from the official record and that its conclusions were “incorrect”.

“The post seems to quote individual months from the BOM record, not even the annual average for individual years. To get an accurate picture you need to consider the full record,” he said in an email.

The official data, when viewed as annual averages, reveals a clear increase in the mean sea level recorded at Fort Denison. It rose from 0.93m in 1914 to 1.01m in 2019, and has continued to rise since.

Other analysis shows a similar picture. A 2009 analysis of tidal gauge data conducted by the NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water also found the mean sea level at the site had risen between 1914 and 2007.

This trend has been confirmed by the US government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the UK’s National Oceanography Centre.

Are sea levels rising?

The social media document goes on to say the Fort Denison data shows it is “incorrect” to assert that sea levels “may permanently rise by 1 to 2 metres in the next 100 years”.

But Alex Sen Gupta, an associate professor at the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, told RMIT Lookout it was questionable to draw such a broad conclusion based on one site.

“I'd be very wary about drawing conclusions about global sea-level rise from a single location”, Mr Gupta said. “If you want a robust answer you would always use as much good data as is available to you.”

Professor Church said sea levels were “rising almost everywhere and they are rising at an accelerating rate”. This was also the case in Australia, he said, pointing to a 2014 academic paper he co-authored which showed an increase in sea levels since at least 1920.

Global sea-level rise is one consequence of human-induced global warming. According to the IPCC’s most recent synthesis report, the global mean sea level increased by roughly 20 centimetres between 1901 and 2018.

The average rate of increase has also grown considerably, from roughly 1.3 millimetres per year during 1901–1971 to 3.7mm per year during 2006–2018.

Based on 2020 policy settings, the IPCC has predicted global warming of 3.2 degrees Celsius by 2100. It estimates 2.7C of warming would increase global sea levels by up to 76cm, while 3.6C would drive an increase of up to 90cm.

AP Fact Check and AAP Fact Check have also found claims about Fort Denison to be false.

Sea-level rise is a common target of climate misinformation, with Reuters, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact and AFP Fact Check all having tackled claims on the subject.

Our verdictFalse. Data from the Bureau of Meteorology shows the average sea level at Fort Denison in Sydney Harbour did not fall by 6cm from 1914 to 2019. Instead it rose by 8.1cm in that period. The document shared on social media claims to use annual figures, but it appears instead to have cherry-picked data for individual months to wrongly argue that sea levels fell over the 105-year period. |

Related News

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Sentient' by Hollie Johnson, Gunaikurnai and Monero Ngarigo.

More information