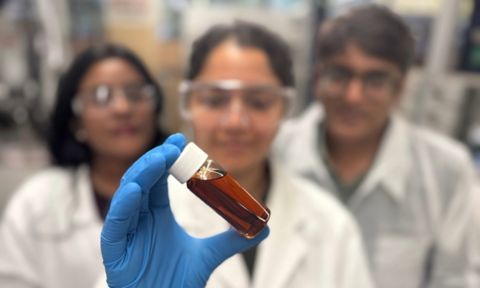

Aussie tech helps make bio-oils for greener industrial applications

Australian technology developed at RMIT University could enable more sustainable and cheaper production of bio-oils to replace petroleum-based products in electronic, construction and automotive applications.

RMIT Centre for Applied Quantum Technologies launches during International Year of Quantum

This week, RMIT Centre for Applied Quantum Technologies (RAQT) was launched by the University.

RMIT strengthens commitment to Asia through renewed partnership with Asia Society Australia

RMIT University and Asia Society Australia (ASA) have announced the second phase of their partnership and launched the renamed RMIT Asia Hub, front door to understanding and engaging with Asia in Melbourne.

RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice shapes justice system reform to better support survivors of sexual violence

The Centre for Innovative Justice (CIJ) has played a key role in shaping the Australian Law Reform Commission’s (ALRC) Safe, Informed, Supported: Reforming Justice Responses to Sexual Violence report.