Water expert joins RMIT Europe

Drawing on extensive expertise in water resource science from Melbourne, Australia, RMIT’s Professor Vincent Pettigrove is set to collaborate with RMIT Europe’s staff and industry partners over the next six months, particularly through his involvement in a research project aimed at improving coastal resilience throughout Europe.

Gas-sensing capsule takes another big step from lab to commercialisation

An ingestible gas-sensing capsule that provides real-time insights into gut health has moved closer to market with RMIT University transferring IP ownership to medical device company Atmo Biosciences.

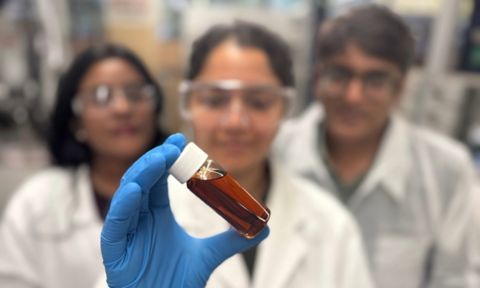

Aussie tech helps make bio-oils for greener industrial applications

Australian technology developed at RMIT University could enable more sustainable and cheaper production of bio-oils to replace petroleum-based products in electronic, construction and automotive applications.

RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice shapes justice system reform to better support survivors of sexual violence

The Centre for Innovative Justice (CIJ) has played a key role in shaping the Australian Law Reform Commission’s (ALRC) Safe, Informed, Supported: Reforming Justice Responses to Sexual Violence report.