Right across Australia, all parts of the social service sector are struggling to provide the skilled, responsive, and healthy workforce we need.

In recent years, a number of Royal Commissions, reviews, and inquiries have highlighted the harms that can be experienced by individuals and communities when any part of the social service sector fails to meet demand for a skilled and capable workforce.

These reviews have recommended various actions, policies and funding interventions to address the problem - but significant workforce shortages and skill gaps persist.

We need to adopt more fundamental and innovative approaches to our workforce challenges. At the heart of our response, we need to start to view social service jobs as part of a modern, rapidly growing industry and profession - with the potential to provide hundreds of thousands of Australians with rewarding careers into the future.

Rather than viewing social services as an industry that is a drain on public resources, where every effort is made to keep costs down, we need to invest in building the skills, capability and productivity of the workforce.

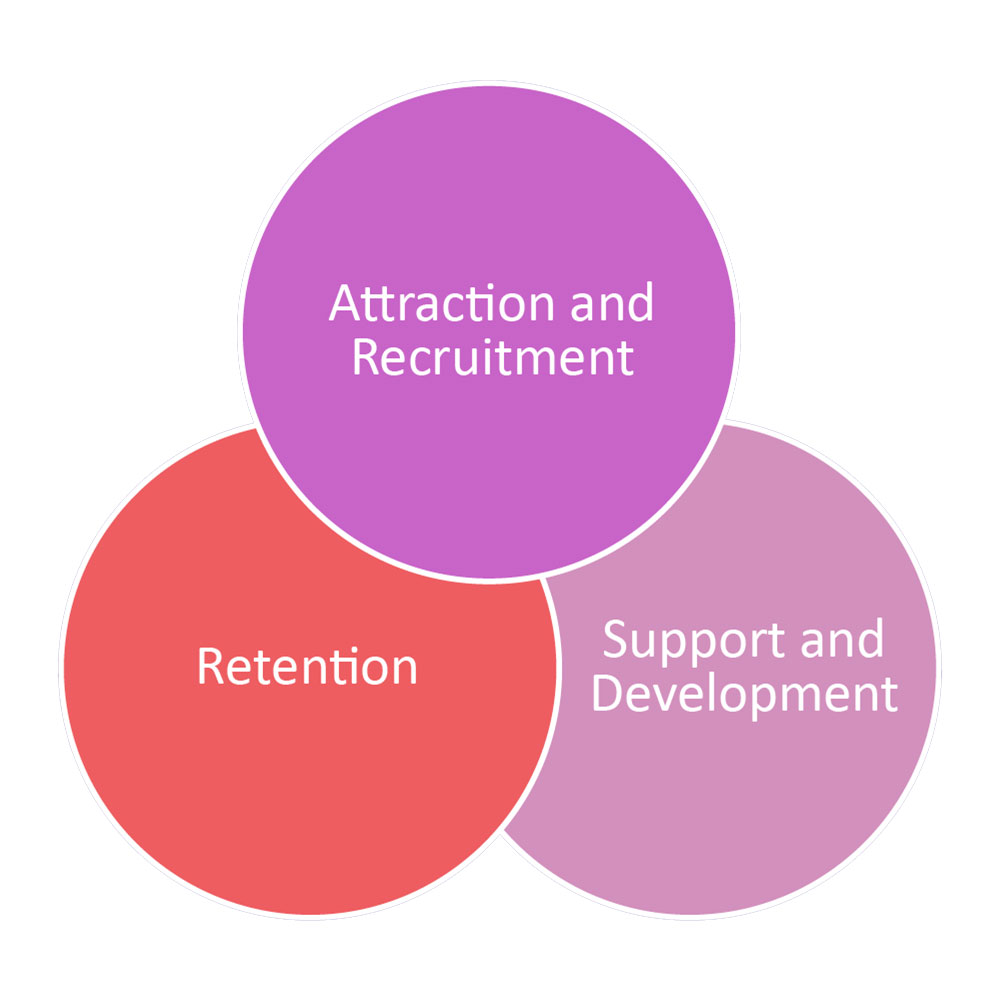

These new approaches need to go to the heart of how we attract, recruit, support, develop and - ultimately - retain the workforce.

Who and how we recruit needs to change. We limit the potential pool of workers by imposing unachievable qualification or experience requirements; fail to recognise the societal changes that make the old “employment after qualification” pathway unrealistic for many; recruit inefficiently; assess job readiness and suitability poorly.

Training pathways and delivery are out of date. Training offerings need to better meet the needs of workers and employers. More flexibility – including on-the-job training – is increasingly important. Flexible training modules targeted at existing workers wanting to upskill and career changers are needed.

Worker safety and wellbeing is being compromised. High vacancy rates push greater loads on to remaining workers. Lack of adequate support and supervision exposes workers to burnout.

Pay and conditions are out of step with cost of living demands and the expectations placed on workers. Career paths are limited. Funding models need to reflect the world as it is, not as it was.

We lack timely data to inform what we should do, and evaluate what we have done. Data is often non-existent or low quality. Analysis is limited. Evaluations are often superficial and findings are not acted on.